Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Expropriation, 2019, bronze, 67 x 22 x 6,5 cm

Ella Littwitz, Mülk, 2019, bronze, 43,5 x 73,5 x 7 cm

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

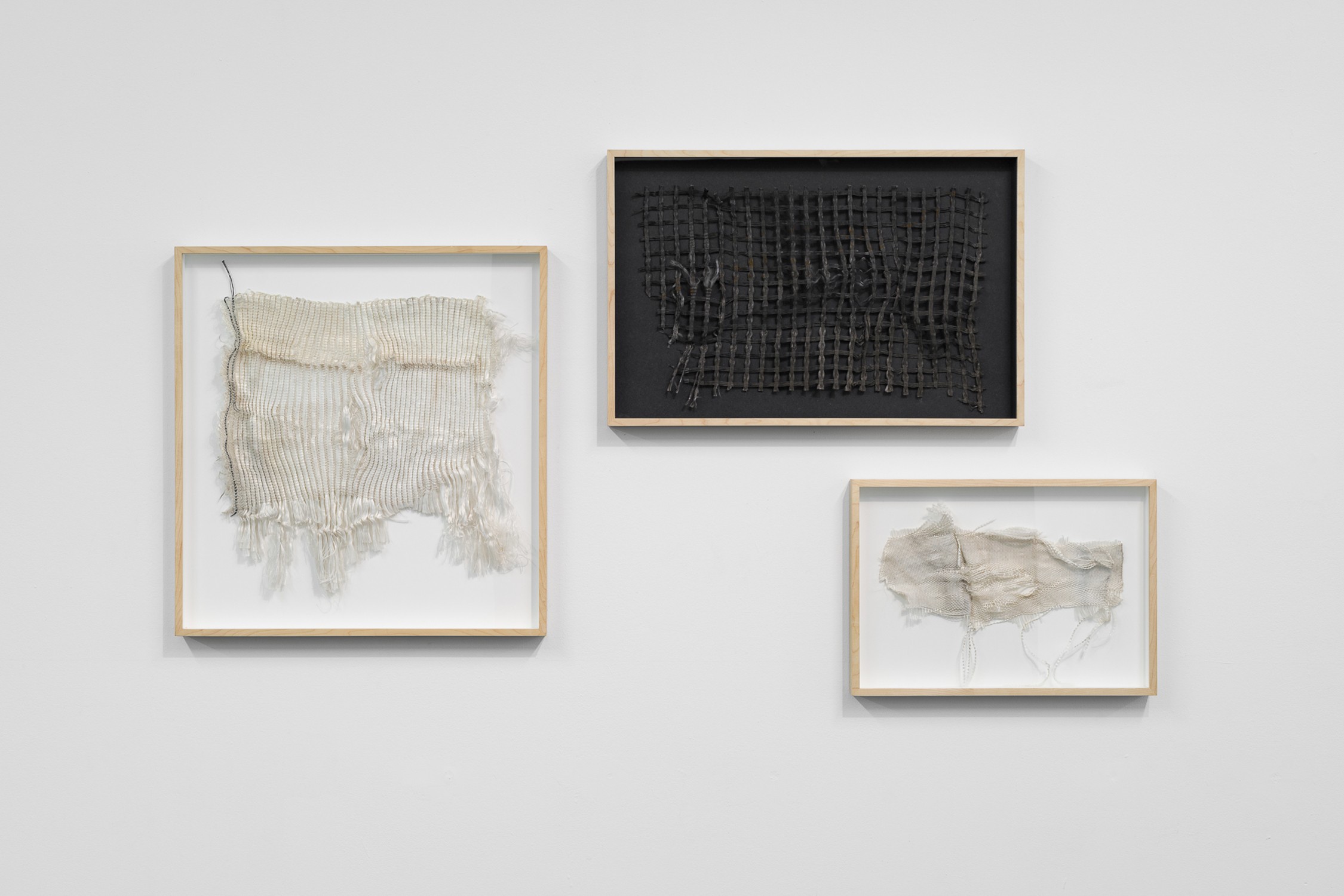

Ella Littwitz, Control (#1) – (#3), 2018, geosynthetic after a tensile test, 62 x 62 cm, 47 x 70 cm, 34 x 48 cm

Ella Littwitz, Facts on the Ground, 2019, installation view, alexander levy, Berlin

The gallery alexander levy is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Ella Littwitz.

In her work, Ella Littwitz explores historical, (geo-)political and national connections of territories. Her home, Israel, herby often serves as a starting point. History, migration, the (re-)construction of national identities and current political discourses are connected through motives of archeology and botany.

The title Facts on the Ground describes geopolitical circumstances and such under international law where a state de facto (in fact) settles on land but is de jure (in law) not recognized. This expression is often used for the Israeli settlement policy in the occupied areas of Palestine.

The exhibition title further denotes a work in the exhibition. The bronze sculpture is a cast made of earth pieces that were found by Qasr el-Yahud at the riverside of Jordan. Although this area is on Palestinian ground it is only accessible from Israel. According to the Bible, this is the place where Jesus Christ is said to have been baptized by John the Baptist. Nowadays, it constitutes the border between Israel and Jordan. Nevertheless, it is controversial on which side of the river Jesus has been baptized; on the shore of the Israeli Qasr el-Yahud or the Jordan Bethania. At the same time, the African and the Arabic tectonic plate, which are in perpetual movement, are colliding here. This is where Ella Littwitz removed twelve chunks of earth that were torn and separated as a result of a flood and transferred them into a permanent material: bronze. Through the artistic interaction with this significant site, connotations of actual political procedures and territorial parameters become visible.

In addition, bronze casts of the pioneer species Dittrichia viscosa are presented. Appearing throughout the whole Mediterranean region this plant thrives as the first one on fallow land as well as on previously damaged ecosystems, simultaneously impeding the sprouting or survival of any other organisms around. Based on botanical facts, Littwitz leads us to questions about the political conflicts in the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel.

Ella Littwitz has frequently dealt with the Mediterranean Sea, which, although connecting many countries, has become a tragic symbol of the gulf between the Global South and the Global North. Through her research, Littwitz has come to know that six million years ago the sea has once been dried out and the Mediterranean region itself was connected through land. Geologists have gathered drill cores from the Mediterranean Sea in the 1970s and have found gypsum and other minerals there which form when salt water evaporates. The work Far As Where Olive Grows, Low As The Bottom Of The Sea is reminiscent of such a drill core soil sample. As the title already implies, this work combines two materials inherent to the Mediterranean Sea: the gypsum and olive waste, which is a consequence of the industrial production of olive oil and a product for heating. Olive trees grow throughout the Mediterranean and historically, they have a special symbolic meaning – their sturdiness stand for perseverance, resistance and peace. This work symbolizes a territory mark – mapping both what is invisible under the sea level and the territory around, which is defined by natural means. As already the older generations used to say: the Mediterranean basin is far as where olive grows.

With the perspective upon a once dried out Mediterranean Sea, the German architect Herman Sörgel has planned a utopian modification of the Mediterranean around 1928 under the title Atlantropa. The desiccation of the Mediterranean Sea enabled through its separation from the Atlantic through dams was supposed to connect Europe and Africa. A dam was to be built on the Straits of Gibraltar, additionally a bridge between Tunisia and Sicily was planned – today’s deadliest part of the sea to separate two continents. This theme becomes the foundation to two series in the exhibition:

The two works 1,101,678 and 102,408 are made of wood, metal and honeycombed geocells, which serve for soil stabilization and erosion protection. The shapes that Littwitz designed with the geocells are based on two main routes that refugees use to cross the Mediterranean Sea. The figures in the titles describe the numbers of refugees that, according to the UNHCR, have passed the Mediterranean Sea on the different routes since 2015 and until today. The uncertain sea routes which have tragically cost and are still costing many people’s lives are in strong contrast to the geocell material itself which symbolizes safety and stability.

A material also used for ground control becomes a major part in her work series Control, for which she subjected various geosynthetics in laboratory tensile tests to a tearing test to check how much force and manipulation is necessary to destroy them.

For the video work Dune Ella Littwitz resorted to footage from the geomorphology department of the Ben Gurion University, which deals with shape-forming processes of the earth’s surface. This material shows recordings from a wind tunnel in which sand storms are staged and analyzed. By recording the storms with a high-speed camera, it was possible to observe the movements of the individual grains of sand. Sand grains break apart, are inexorably carried by the storm. Dunes represent the fastest process of land forming and territorial change, as the sand keeps on migrating. The sandstorm has no human borders, it continuously remains in a free flow and naturally surpasses all barriers and boundaries.

For the current exhibition, Ella Littwitz puts her focal point on the territorialisation. Sculptures and a video tell stories of borders and their transgression, they tell stories of people without naming them. Within these narrative works, she moves through history like an archeologist.