Frank (2025) permeates the exhibition space. The cracking and popping of the sound work affect you immediately; though they cannot be escaped, they cannot be located. The source is hidden from view behind the partition wall, and what is heard are the sounds of bubbles bursting in the synovial fluid. Complex to grasp yet defining the exhibition, Frank reflects a functional relationship that is relevant to all exhibited artworks: it represents what usually occurs behind the scenes in the art world but is required for art to be publicly experienced. Specifically, it refers to the physically demanding labor of art handling. This work has become central to Fabian Knecht’s practice, and to be able to continue doing it, he regularly visits his chiropractor, Frank. At the same time, he incorporates Frank into the production of his artwork, as it is the chiropractor who extracted these sounds from the artist’s strained body.

The two visible works, Lachen ist verdächtig (Ist Fabian sich sicher, dass die Stoffe bunt sind?) (Laughing is suspicious (Is Fabian sure that the textiles are colorful?), 2025) and Siegfried (2025), are crafted by the hands of others and transferred to the realm of art by Knecht. Since 2022, he has employed this strategy in his support of Ukrainian civilian resistance against Russian invasion.[1] The amorphous textile mass, spilling from a trolley and seemingly spreading into the room, is composed of camouflage nets, knotted together at the beginning of the war by those not who were not called to the front lines. They repurposed household fabrics and weaved them into handball-goal and fishing nets. The significance of this collective labor lies less in its military utility – the fabrics are too absorbent for this purpose, become difficult to handle when wet and prone to mold, and some of the colors stand out too much – than in its community building effect. By exchanging these on site for military-grade camouflage nets, Knecht contributes to protecting critical infrastructure.

Knecht transports the nets into the art world himself. To import this cargo, he has crossed the EU’s external borders numerous times. By now he knows which customs fees and waiting times apply at different crossings and which documents allow him to bring the questionable textile piles into the country. Museum stamps and a German passport make for an easier passage. Until recently, he has installed the nets on museum walls, sometimes indoors, as at the Städtische Galerie Wolfsburg; sometimes outdoors, as at the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow; and in front of the glass façade of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin during the Festival of Future Nows. This time, he explicitly presents them as transported goods, thus bringing his own infrastructural work to the fore.

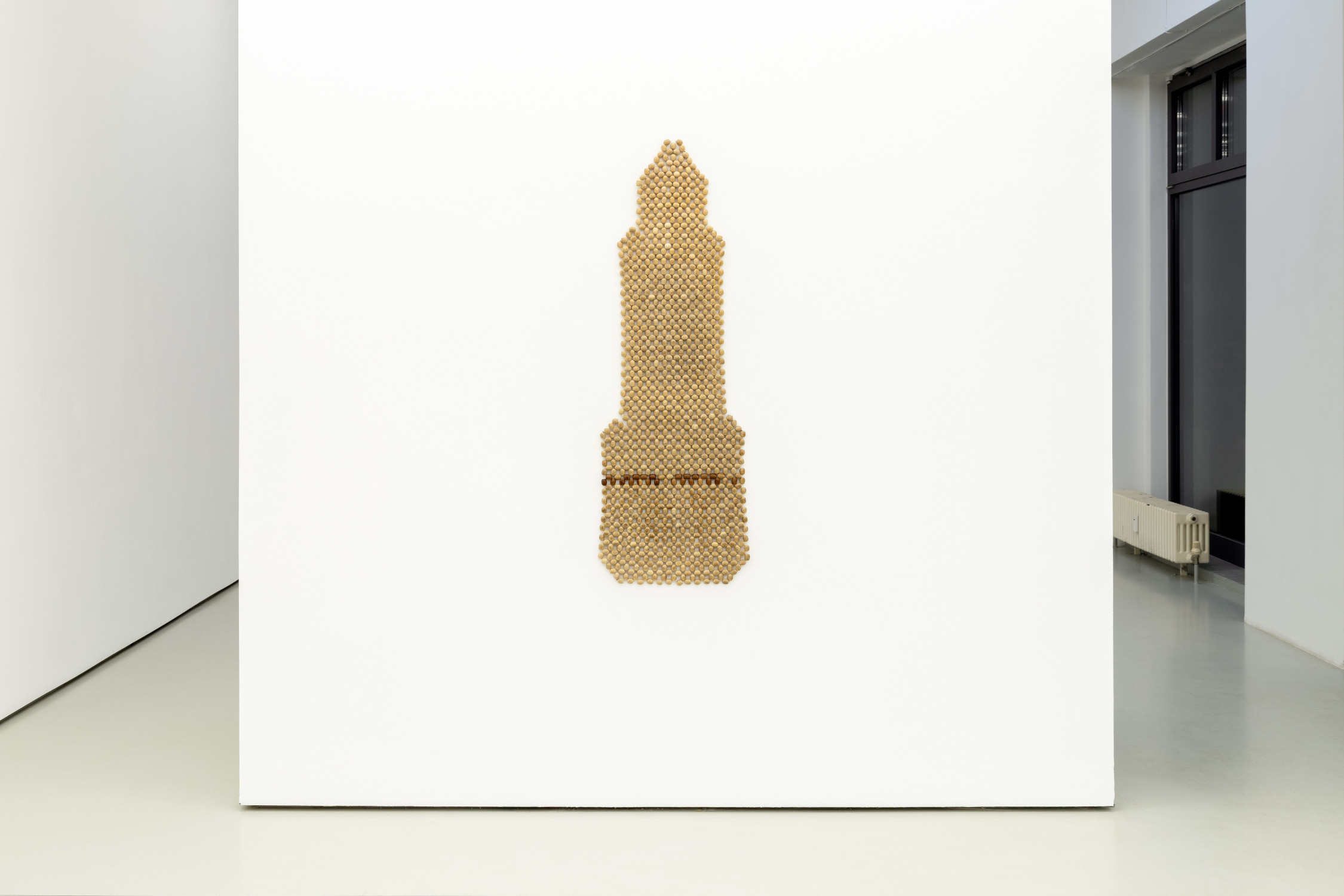

When acute back pain flares up during the long journeys – Knecht has travelled to Ukraine nineteen times since 2022, covering around 63,000 kilometers in his VW T5 – a wooden beaded seat cover provides him with immediate relief. Now worn, the artist hangs it in the center of the gallery space, a nail fixed through it from the back. Unlike Siegfried’s, the almost indestructible hero of the Nibelungenlied (The Song of the Nibelungs), whose name the work references, the weak point of the artist’s body is not between the shoulder blades, but just below the left one. Yet Siegfried alludes not only to bodily vulnerability, but also to Sieg (victory) and Frieden (peace).

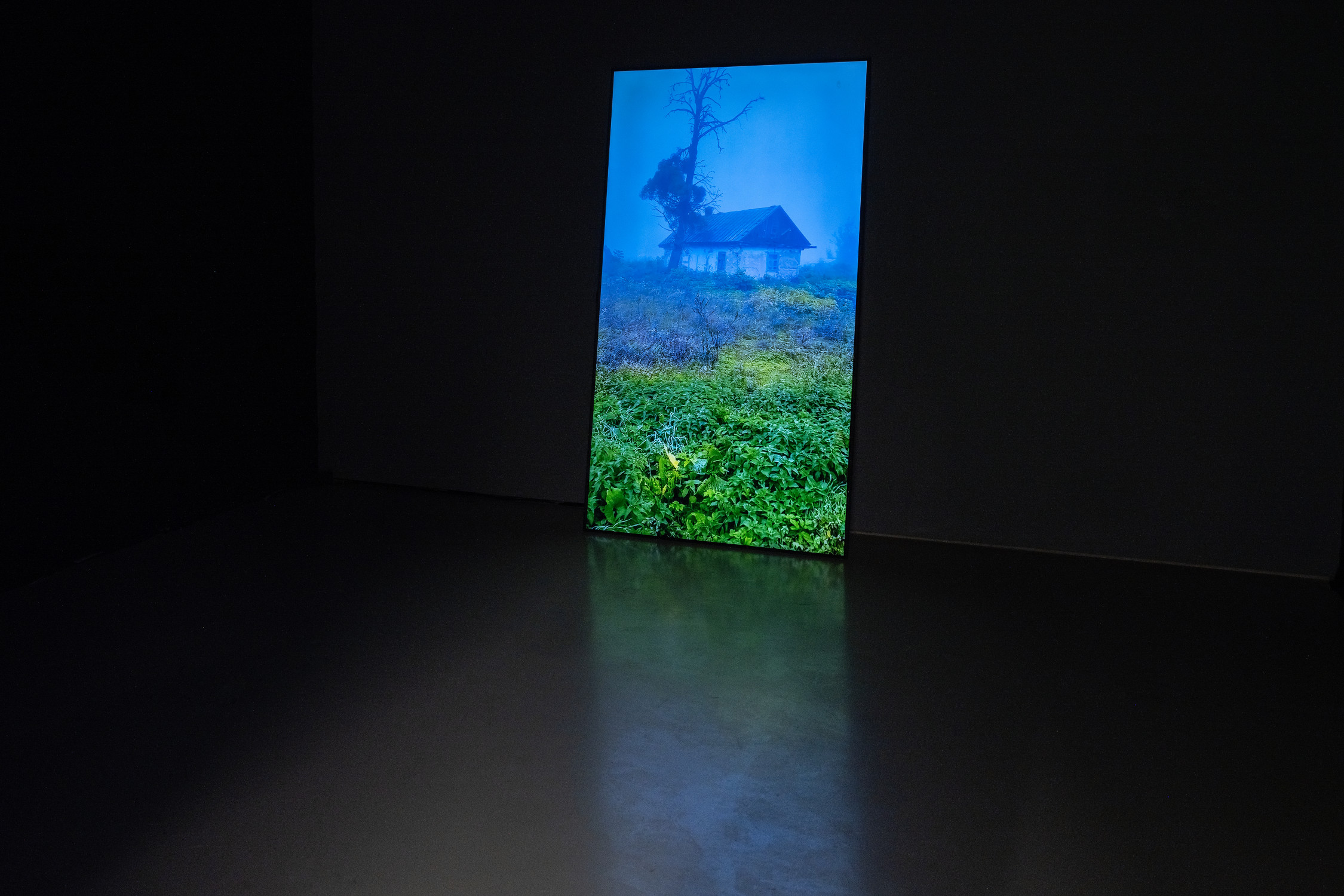

War, in turn, is experienced by many in the West only at a distance and through media. “Looking from the west,” historian Timothy Snyder observes, “we tend to think of war as a movie, something that comes and goes quickly, where there is either absolute devastation or the quiet peace of final victory. But […] in Ukraine, is something else, something essential: people who do what they are supposed to do, but who also want the beautiful and the whimsical in life.”[2] Der Weg des größten Widerstandes (Path of Most Resistance, since 2022), the work presented in the basement, captures this reality in video. In this ongoing project, Knecht documents his trips in Ukraine with an iPhone – through the windshield of his VW T5, from other cars and through windows, in interiors, across the countryside, and in cities. Now over an hour long, the work portrays a country in which war has become normality and normality has become shaped by war: soldiers’ graves, flowers, bombed houses, a Chihuahua in jeans and national colors.

In Frank, Knecht makes explicit the infrastructures underlying his artistic practice and solidarity work in connection with the war in Ukraine, focusing on the transportation of the nets and the reproductive labor associated with it. What remains unseen, yet integral to his practice, is the financial support made possible through his art sales. By skillfully navigating value and meaning systems within the art market, Knecht achieves tangible social effects: strengthening Ukrainian resistance. In doing so, he exercises infrastructural criticism: he treats the art system as a material context that is flexible enough to be used as a network for humanitarian redistribution.[3] At the same time, he points with great clarity to the importance of infrastructure for sustaining life in Ukraine, which is under threat by Putin’s fascist aggression.[4] In one of his first works from 2022, Knecht photographed the Desna Bridge, bombed by Russian military, from a seemingly inescapable central perspective.[5] By continuing to transport camouflage nets to Germany more than two and a half years later, he makes visible what marks life in Ukraine. There, shipment of defense materials is a part of everyday life, with such items being sent across the country and right to the front lines just as other mundane online shopping articles are.[6]

Text by Antonia Kölbl

[1] Sebastian Frenzel, “Künstler Fabian Knecht: ‘Ich kämpfe gegen Kriegsmüdigkeit’,” in Monopol, September 4, 2023, https://www.monopol-magazin.de/fabian-knecht-ukraine-wolfsburg; Alona Karavai, “The Protection of Protection,” 2025, available at artmap.com, https://artmap.com/mocak/exhibition/fabian-knecht-2025; “Path of Most Resistance,” https://fabianknecht.de/.

[2] Timothy Snyder, “The Hands: Running a race in wartime Kyiv,” in Thinking About…, September 13, 2025, https://snyder.substack.com/p/the-hands.

[3] Marina Vishmidt, “‘A Self-Relating Negativity’: Where Infrastructure and Critique Meet,” in Broken Relations: Infrastructure, Aesthetics, and Critique, edited by Martin Beck, Beatrice von Bismarck, Sabeth Buchmann, and Ilse Lafer, Leipzig: Spector Books, 2022, 29–44.

[4] On the fascist dimension of the Russian war, see, among others: Timothy Snyder, “Putin’s genocidal myth: The foolishness of fascism, revealed in the Carlson interview,” in Thinking About…, February 11, 2024, https://snyder.substack.com/p/putins-genocidal-myth.

[5] Fabian Knecht, Desna Bridge, 30 April 2022, 2022, photo, https://fabianknecht.de/works/desna-brucke-30-april-2022-desna-bridge-30-april-2022-2022/. On the central perspective in Knecht, see: Raimar Stange, „On the (Aggressive) Reality of Art. Raimar Stange on selected aspects on the artistic work of Fabian Knecht,” in Antikörper Antibody, edited by Alexander Levy and Isabelle Meiffert, Bielefeld/Berlin: Kerber, 2018, 19–24.

[6] Charlotte Higgins and Mariana Matveichuk, “Car bumpers, homemade pies … no weapons allowed: the unstoppable postal service keeping Ukraine going,” in Guardian, November 11, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/11/car-bumpers-homemade-pies-no-weapons-allowed-the-unstoppable-postal-service-keeping-ukraine-going.