The gallery alexander levy is very pleased to present four artists who examine the same areas of tension of our time with differing approaches in the exhibit The World is Stable Now.

“Because our world is not the same as Othello’s world. You can’t make flivvers without steel – and you can’t make tragedies without social instability. The world is stable now.”

The title of the exhibit is found in this central quote from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The dystopian vision of a ‘stable’ world, as described by Huxley in his novel, seems, among other things, like the antithesis to the works collected in the rooms of the gallery, which are conspicuous in their thematic preoccupation with change, transformation and reinterpretation. The stability of a world edifice claimed in the title is counteracted by the more or less obvious fragility of the same, which the artists of the exhibit position at the centre of their respective pictorial terrains – theatrical backdrops, urban facades and cool corporate identities. With the reclamation of the political and cultural phenomena of our present, our gaze is directed to the cracks in its foundation, the contradictoriness and potential of which needs to be examined more closely.

Cruising the decay unites various works of Diana Artus on paper. They are fragments of an imaginary route through the city along images of fragile moods and states. They present not only the urban backdrops though which we move on a daily basis, but especially their fundamental instability, ephemerality and indeterminacy. The city is presented here as ‘Terrain Vague’, as a place that can be described both through errors and through absence, in such imperfection and openness, but at the same time as a constant reservoir of new possibilities. This is reflected in the formal approach of the artist, who subjects the photographic materials she has collected in cities to processual transformations and disruptions, whereby architectural bodies and urban situations are alienated in a surreal fashion. The ‘passing’ of these images is similar to that of the observer; the gaps, dislocations and blurring in the structure of meaning correspond to his projections.

Fabian Bechtle’s room installation Holy Land revolves around a replica of the ‘Holy Land’ erected in the 1950’s in the USA from plywood, wire mesh and stone, of which only the officially inaccessible, overgrown remnants remain today. Once conceived of as a Christian theme park, the place has been abandoned since its closing in 1984 and is classified as an unsafe area – it has already been the venue for horrific murders and various supernatural phenomena. In his installation, Bechtle stages fragments of the present day perception of this formerly whole and holy miniature world anew using videos, found pieces and a central gate sculpture, which has now evolved into its opposite – the definition of a terrible, cursed place. A displacement of the meaning with drastic consequences, which is exclusively due to the fact that the manifestation of a belief transformed into a backdrop will at some point be left to itself.

The Atlas Film Studios in Morocco, in which films such as Gladiator, Kingdom of Heaven and Prince of Persia were filmed, form a fantastic stage at the edge of the Sahara, which, during the filming breaks, apart from a few tourist groups, is represented as a deserted and increasingly disintegrating wasteland, a cemetery of blockbusters. These fragile film backdrops built of flimsy material become the protagonists of Lilli Kuschel’s video work Atlas Cinema, in which she has reshot selected scenes from films produced here and scored them with the sound of the respective original. Location, settings and editing sequences correspond one to one with those of the original film sequences, but there are no actors – it is up to the imagination of the viewer to breathe life into the images of ghostly emptiness and to allocate the voices heard to an event.

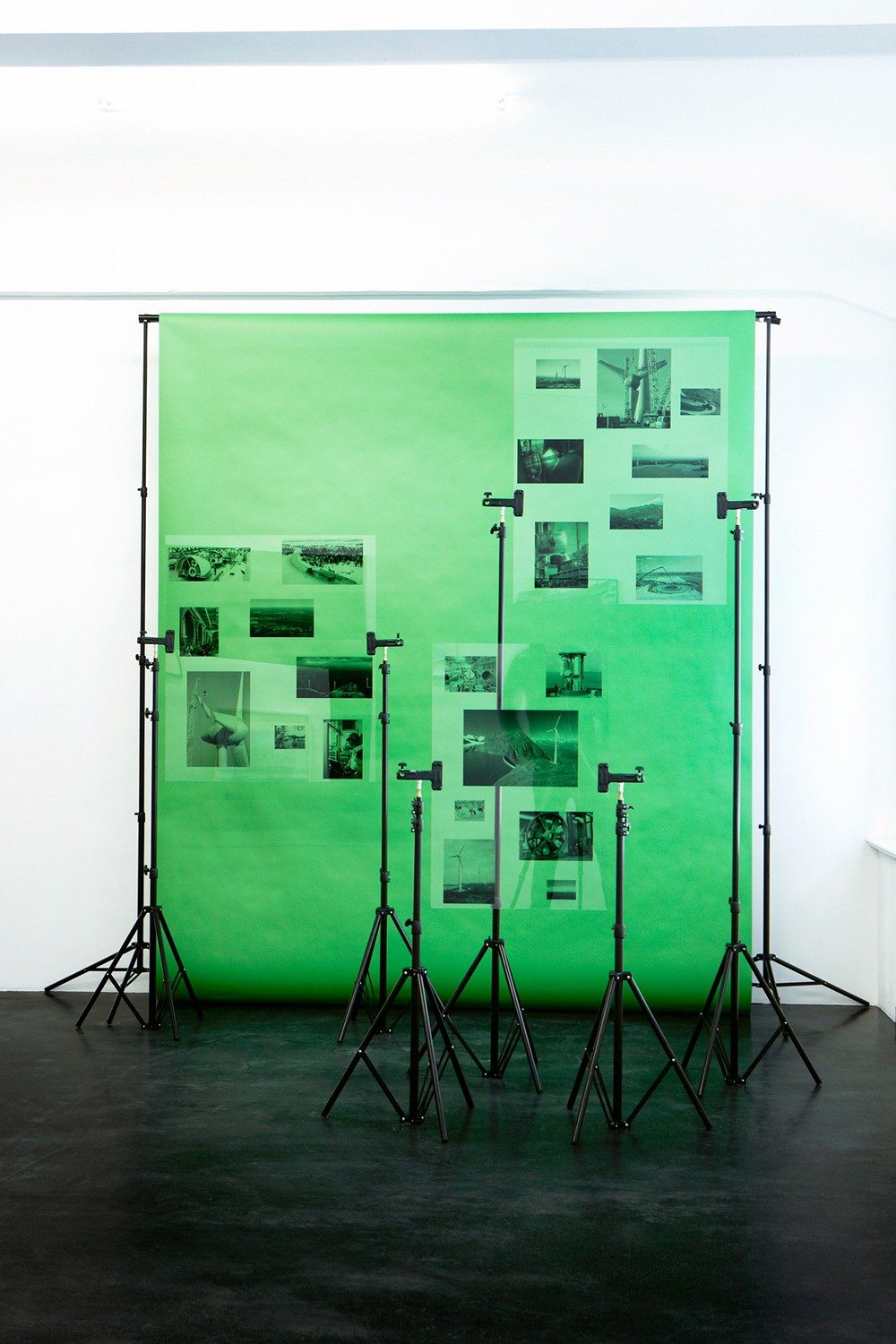

In his Industria Mirabilis installation, Leon Kahane shows photographs from the image brochures of a globally active wind turbine manufacturer. Kahane’s contribution is a studio set modified for his purposes. Against the background of a green screen installed in the exhibit space, he also creates aesthetic and content- related relationships between geographically distant places and ‘events’ that advertise and question the ‘promises’ of progress.

The title of Kahane’s work is derived from a poem by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz about the ‘Phosphorus Mirabilis’ – miraculous phosphorous. According to the most recent studies, the worldwide supply of phosphorous may already be exhausted in 50 years.