At the age of only 17, Meret Oppenheim (*1913 Berlin †1985 Basel) wondered, if mathematical equations had roots, where then the rabbits are – and collaged X=Hase (X=rabbit) into her exercise book. The artist’s entire work and thinking bespeak an independence and resistance that go against all logic as well as academic and social norms. Oppenheim’s œuvre is symbolic of the mysterious, the hidden, the unconscious and the unexpected, offering an astonishment that is driven by curiosity – just as in the case of the little girl in the painting Die Waldfrau, who alone in the forest discovers a huge, mythical female creature with a dragon’s tail. Here, nature becomes a mythical place of human-animal primal forces. Her affinity for the works of psychoanalyst C.G. Jung allowed her early in life to delve into the profund spheres of the human mind and gain an understanding of the unconscious collective structures of the soul.

Oppenheim’s search for an autonomous identity and unrestricted artistic expression was based on a ravenous desire for freedom. A desire which caused her to break with the surrealistic circle in Paris in the 1930s, celebrating her first big success, the “fur cup” (Le déjeuner en fourrure), a key work amongst the surrealistic objet trouvé. Having been categorized as a muse and cut back in her creative spirit, the artist faced a yearlong creative crisis, that she would only be able to overcome by the 1950s in the lively and creative climate of Bern among like-minded fellow artists like Daniel Spoerri and Dieter Roth. Her personal ideology of overcoming boundaries, which in her early work was shown in the deconstruction of patriarchal femininity, was developed into a holistic thesis about human androgyny – the unity of the feminine and masculine spirit underlying every artistic creation – and thereby revolutionized the image of the – historically trimmed of her male part – female artist.

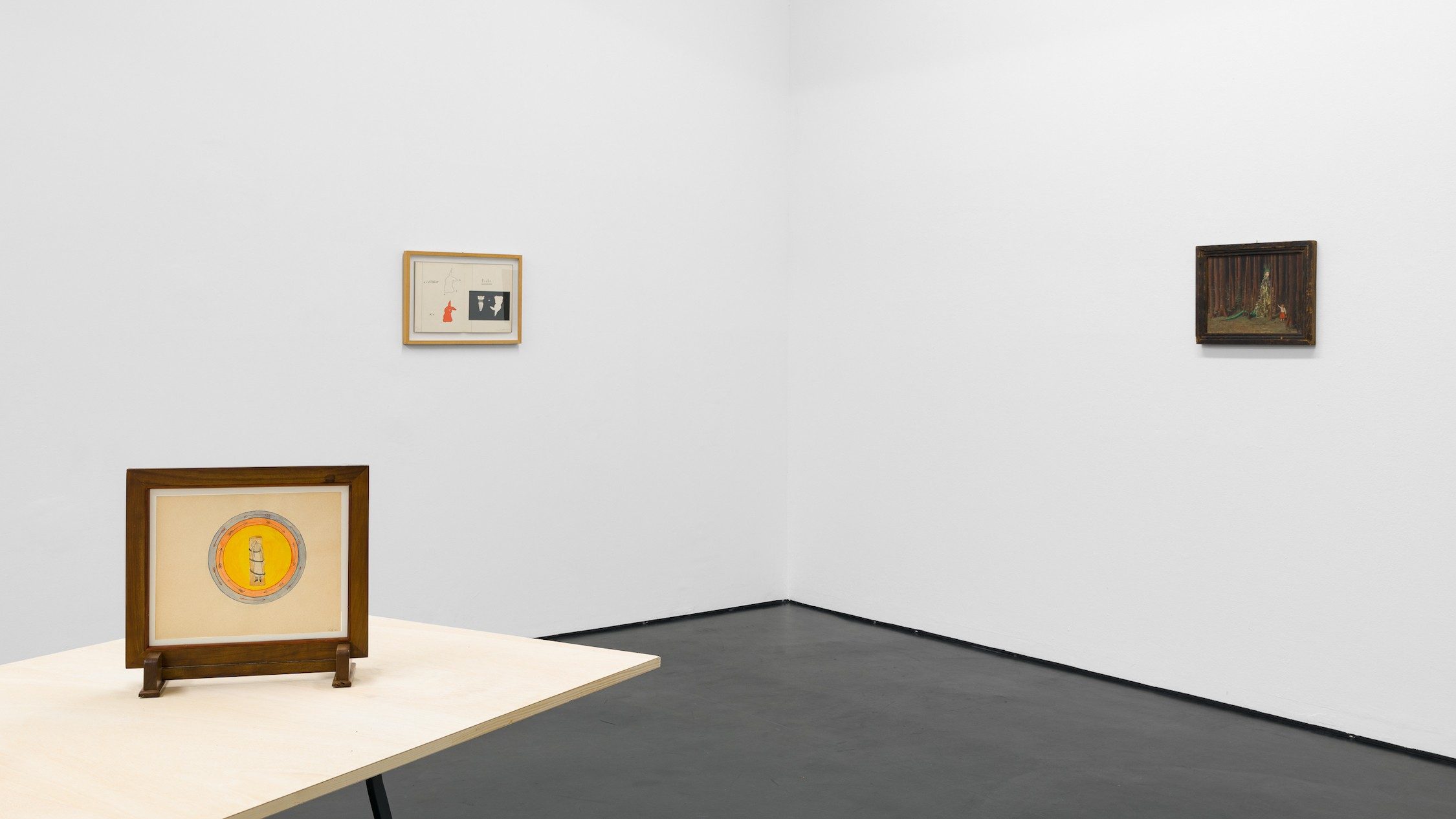

Oppenheim never wanted to be restricted to an identity, style or medium in any way. Her cross-genre and materialistically diverse works testify to an imaginative, poetic and ironic interplay of free and applied arts, such as jewelry, fashion and furniture designs. Despite the rejection of a stylistic classification, the somatic, materialistic and associative aspects, that Surrealism has pushed into the foreground in the beginning of the 20th century, remained intrinsic to her work: object-like assemblages and ludicrous combinations of materials enter into a play with sensations, corporeality and alienation.

The paintings and drawings oscillate between geometric forms, abstract landscapes and imaginative constructs – ephemeral status reports between dissolution and formation, interior and exterior spaces, mental ideas and tangible forms. The artist furthermore shows herself as a lyricist and poet who with associative word games strives to dissolve the boundaries of the dimensions of her works.

In her game of perception for the eyes, senses and mind, Oppenheim expresses the urge for metamorphosis as a central strategy: dichotomies between nature and culture, masculinity and femininity, spaces, structures and genres dissipate. The expansion of identity constructions facilitates an actuality to Oppenheim’s œuvre, especially for contemporary artists. “Freedom is not something you are given, but something you have to take”, she stated in her speech during the presentation of the Art Prize of the city Basel in the year 1974 – a plea, that preceded its time and is still holding an unabated presence.

Oppenheim received her first major retrospective in Stockholm, followed by exhibitions in Solothurn, Winterthur and Duisburg in 1974/75, the Art Award of the City of Berlin in 1982 and her participation at the documenta 7. In 2013, a further retrospective at the Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien in Vienna, Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and Lille Métropole musée d’art moderne, d’art contemporain et d’art brut in Villeneuve d’Ascq took place. In 2021/22 another comprehensive retrospective will honor Meret Oppenheim’s artistic work, starting at the Kunstmuseum Bern, then moving to the Menil Collection in Houston and ending at the MoMA in New York. The alexander levy gallery honors the artist’s eclectic oeuvre and her independent artistic position with a solo show from November 2 to December 20, 2019.

Text by Marleen Linke

A Conversation between Thomas Levy and Alexander Levy

A: When did you first become aware of Meret Oppenheim?

T: In 1977. At that time, the Academy of Fine Arts in Hamburg was hiring guest professors, and they managed to get Meret Oppenheim amongst others. I had a large gallery in Hamburg, in Tesdorpfstraße, and thought, if such a famous artist as Meret Oppenheim is here in the city I’d offer her an exhibition. So I made an appointment with her. Apart from Man Ray’s well-known photo, Érotique Voilée, of Meret at the printing press and the “fur cup”, I didn’t know much about her work. And I guessed she was about ninety years old. She was, though, sixty-five then, and as she heard that I wanted to meet her, she guessed I was ninety, although I was thirty years old. In this respect, we hit it off really well because we were actually young! She wasn’t happy at the academy, so she moved into my guest flat two weeks later.

A: When did you do the first exhibition together?

T: The first exhibition was in 1978. She sent me her whole portfolio for the show. We catalogued and photographed it all and produced an extensive monography. We also made a contract, although I’d never done that before in my life with artists. She wanted that though, as she could rarely say “no”, although she always wanted to when people asked her to do something. Then, every time she didn’t want to, she could pull the contract out of her bag and say, “I have a contract with Levy, ask him.” If she liked who was asking, the contract didn’t appear.

A: So how long did she live at yours?

T: I think about 3 months. She didn’t particularly like being a guest professor in Hamburg. She always slept till about midday, and we usually went to St. Pauli in the evenings, to the “wicked bars”, as she always called them. She was quite well-known in Hamburg. In 1978/79, there was a big Baselitz exhibition in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, and we went to see it together. The TV cameras were focused on her immediately because of her extraordinary appearance. She was wearing a paper jacket or something that she had designed herself. It was all exhilarating.

Daniel Spoerri has a similar story from the 1950s. He was staging Picasso’s play, Desire caught by the Tail, which Meret re-translated as she didn’t think Paul Celan’s translation worked. She also played a curtain in the piece. Spoerri told a photographer that Meret was present. The photographer didn’t know who she was. When Spoerri mentioned the “fur cup”, he went off and immediately photographed Ms Oppenheim. That’s how it is with Meret: people only know those two works.

A: For her, it was a boon and a bane at the same time, wasn’t it? The “fur cup” made her famous but also reduced her to just that.

T: Yes, but luckily, she didn’t cover objects with fur her whole life.

A: That’s the crazy thing about it: she would certainly have been successful as a “fur artist”. Apart from this iconographic piece, she could have filled a whole museum exhibition with fur objects or installations. Her œuvre is, however, multi-faceted. I read in an interview that when she had developed an idea, she had to start on another one immediately. And as soon as she realised that she was producing something similar, she abandoned it and started something new.

T: As we started working together, people said that she didn’t have a style. She is an ideas artist, as were her friends, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. In my opinion, the paintings of these three artists are not so pivotal. Far more critical with them are the ideas and drawings, and the objects they developed from them, which accurately describes the avant-garde today. Times have changed since then, and today everyone is talking about Meret Oppenheim. She’s being honoured with huge, world-wide retrospectives ending at the MoMA in New York in late 2022.

A: Has she talked about her work, explained it? Some of her works and titles evoke a wide variety of associations and sometimes would need an explanation.

T: She worked intensely with the subconscious and developed many of her works from her dreams, which she put down on paper or canvas. If someone was really interested, she would talk about where certain things came from. But on the whole, this wasn’t so important for her.

A: Would you describe her as a Surrealist?

T: She only worked for a time with the Surrealists, actually three years. There are Surrealist works, but she is not a Surrealist. And she took part in large-scale exhibitions with them in 1936 at Galerie Ratton in Paris and in 1939 at the gallery of René Drouin and Leo Castelli in Paris. She was a long-time close friend of André Breton and other prominent figures in the Surrealist group, but especially with Elisa Breton. They valued each other and discussed art with each other, probably when they were eating and drinking together.

Why are you interested in exhibiting Meret Oppenheim? Meret always showed only in avant-garde galleries, so that fits well – but what motivates you to show her?

A: I grew up with the spirit of Meret Oppenheim. For you, she occupies a significant artistic position, and I understand that, of course. She had a powerful influence on art. She was and is a trailblazer, especially for female artists. It also occurred to me how little of her work is available for the public to see, so I’m very interested in showing her works here. There are also parallels to some of the artists in my programme. As an ideas artist, she operates in a similar way to the gallery artists. Furthermore, there are cross-overs in dealing with the themes of perception and nature. I don’t think I’m going to show an older classical position, but one that is still very relevant today.

T: She was, still is, and, I think, always will be “avant-garde”.

(The interview was held in October 2019. Thomas Levy is running his gallery in Hamburg since 1970 and is representing Meret Oppenheim since 1978. His son Alexander Levy opened his gallery in Berlin in 2012 and is exhibiting Meret Oppenheim for the first time in 2019.)